environmentalism

ALA PLÁSTICA: the ideal spectacle of the Global South?

Sunday, August 23rd, 2020 | Allgemein | No Comments

By Maria Rocio Naval

- Introduction – collaborative art and the benefits of a transcultural perspective; democratic “critical zones”: climate activism and its colonial continuities

- ALA PLASTICA – who are they and what do they do?

- The AA Project – levels of social engagement; collaborative art practice as a site for environmental activism

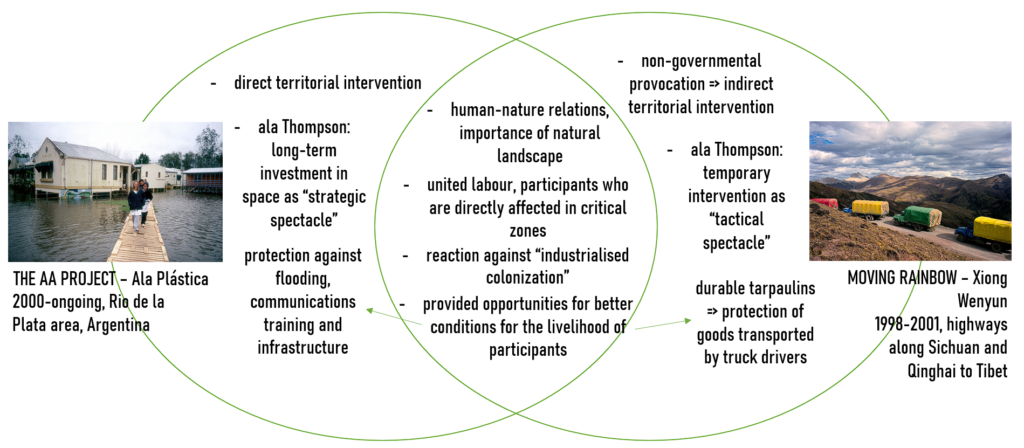

- Comparisons – Park Fiction; Moving Rainbow

- Institutionalisation – GROUNDWORKS, Equation of State

- Conclusion – issues to consider

- Bibliography

source: Ala Plástica website gallery

INTRODUCTION

Collaborative art and the benefits of a transcultural perspective

This visual essay aims to explore Ala Plástica’s use of collaborative practice as a potential model for other artist-environmentalist movements in the Global South. To do so, a critical theory of socially engaged art should be considered, specifically in a global and transcultural context. Grant Kester (professor of Art History at the University of California, San Diego and founding editor of critical journal FIELD) and Monica Juneja (art historian and professor of Global Art History at the University of Heidelberg, Germany) have provided some key points regarding collaborative art practice as a site for experimentation in a social setting and how transcultural aspects can help bear insights to specific socio-political circumstances in certain areas (i.e. colonial continuities and issues of decolonisation) and how that, in turn, influences art production and collaboration/participation.

Here is a summary of Kester’s main arguments from his book “The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context” (Duke University Press, 2011):

- collaborative art is a mode of ethico-representational engagement

- works like Park Fiction and the AA Project (by Ala Plástica) exhibit the desire to work through experiences in an experimental manner

- the definition of art is in constant flux and must therefore depend on the social conditions of local history

Kester reviews the fluctuations of what can be defined as art by looking at how it has evolved throughout time. He notes that contemporary art for example, its attempt at a destabilisation of power exhibits a paradigm shift, writing:

“Art is trapped within the oscillation between challenging the institutional power and being institutionalised.”

Juneja further writes in her article “A very civil idea…Art History, Transculturation, and World Making – With and Beyond the Nation” (Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 2018) that an ever-evolving art history must:

- examine the specific dynamic between distance and proximity, and pay greater attention to multiple relationalities that unfold beyond the coloniser-colonised divide

- according to Partha Mitter, direct attention to how actors on these sites (referring to territories) (…) sought to make its civilisational aspect serve as a critique of colonialism

In correspondence to Kester’s idea that collaborative art is a mode of ethico-representational engagement, Juneja makes it a point to say the following about transculturation:

“The idea of world-making needs to be anchored as a perspective with which to shape [art history] where the relationship between ‘archive and vision’ is itself an ethical responsibility.“

Democratic “critical zones”: environmental activism and its colonial continuities

In order to look at Ala Plástica’s artistic approach to collaboration, it would be imperative to branch out beyond the scope of art history and cross into broader disciplines. For this investigatory purpose, we should consider Mihir Sharma’s thoughts on colonial continuities in environmental activism in the Global North as well as Bruno Latour’s philosophies on humans and their relation to the environment to recognise the principal contexts in which Ala Plástica works.

Mihir Sharma is a writer and academic who offers lectures on climate activism in the Global North and explores this phenomenon as a method of decolonisation that, paradoxically, has difficulty fully addressing its euro-centrism. However, he notes that key elements remain the same for climate movements in both the Global North and the Global South: where (a) climate change and justice is a social issue and that (b) environmental movements must be based on community involvement in addition to individual motivation. To support this, I have compiled a summary of Sharma’s positions on the decolonisation of climate activism in the Global North in a list of bullet points:

- What is meant by environmental activism as a method of decolonisation -> aspiration toward programme of reparations, oriented toward present-future politics using past actions (including effects of colonialism and its continuities) as reason, involvement of international relations in solving a global problem

- There is an attempt at the development of anti-colonial thinking in Western environmental movements through collaborative projects and collective reflection

- Activism is a movement generated for the community, rather than the individual

- The idea of “climate justice” is brought forth by a culmination of dialectics where it is posed as a social issue, where the fight against capitalism, racism, etc. is imperative to achieving climate goals

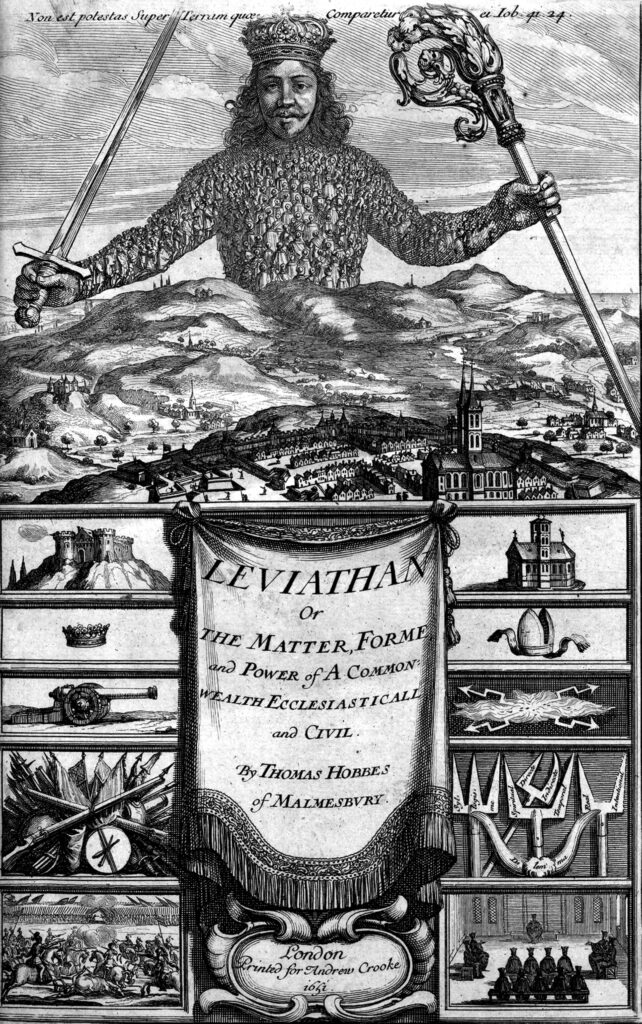

When it comes to Ala Plástica, an artist-environmentalist group based in Argentina, their approach to “anti-colonial thinking” encourages a holistic transcultural world-view in climate discussions by offering collective reflection. Ala Plástica achieves their approach through collaborative artistic intervention. However, with collaboration and inter-human relations comes a question of democracy and how that connects to our perception of a physical earth/environment. Latour, for example, talks about the Anthropocene in terms of human engagement with nature and explores its democratic character, thereby implicating non-human entities as being influenced by inter-human politics (another topic heavily discussed in socially engaged art theory). His arguments are summarised in the following bullet points:

- There has been a “breech” between politics on globalisation (of nature): the essential link between conservative revolution and its denial of the new climate regime leads to disorientation and issues of identification, in which territories affect democracy and vice versa.

- The “Terrestrial” serves as a visualisation of terrain where politics is being exerted and can be defined as a democratic critical zone.

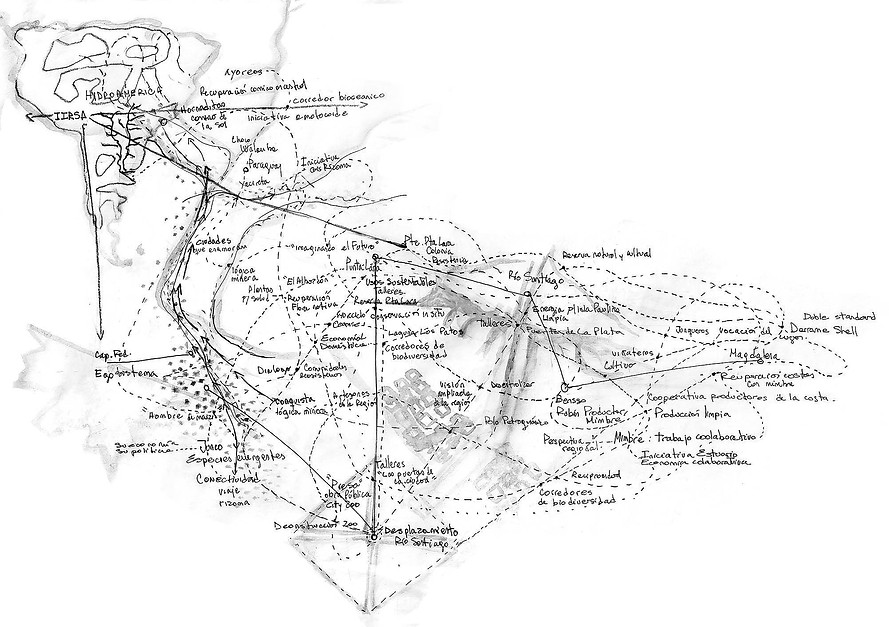

- Art exists as an exploration of connections and relations between humans and non-humans. A historical example of art being used as a medium of exploration of human control over non-human entities is Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes.

source: Wikimedia Commons

Issues of control, as exemplified by Latour, exhibit interesting parallels to the discourse about artist/collaborator/participant control in socially engaged art. How that ties in with democratic aspects that extend beyond the spectrum of human politics is fundamentally explored in Ala Plástica’s “rhizomes” (Fig. 1.) as a visual map of what Latour calls “critical zones”.

ALA PLÁSTICA

Who are they and what do they do?

“Ala Plástica is an art and environmental organization based in Río de la Plata, Argentina that works on the rhizomatic linking of ecological, social, and artistic methodology, combining direct interventions and defined concepts to a parallel universe without giving up the symbolic potential of art.”

Ala Plástica website

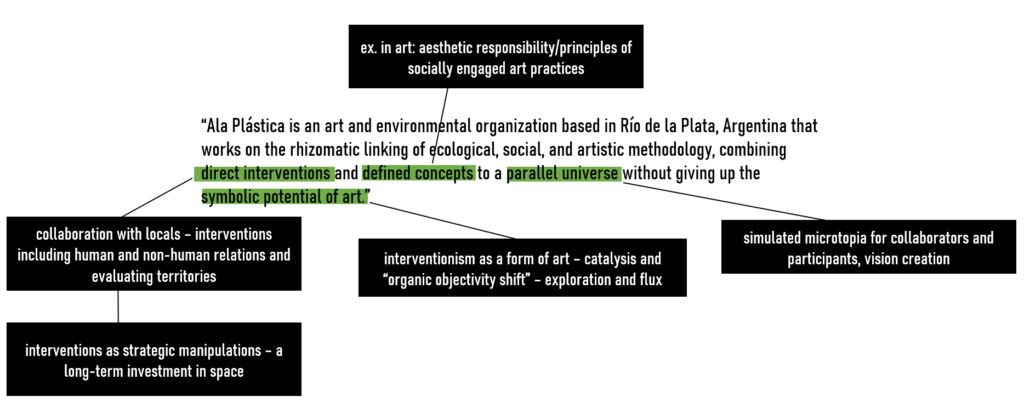

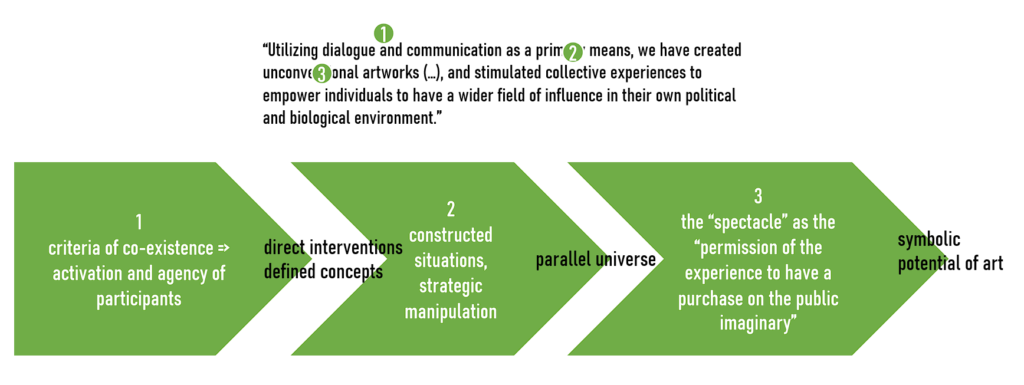

This is a quote taken directly from Ala Plastica’s website explaining in the broadest sense what they do and the intentions of their projects. They claim to enact socio-ecologlical change in an artistic and experimental manner. In order to underline their standing in contemporary socially engaged art, I have dissected their artist statement in the form of a diagramme:

I connected their terms with ideas from pioneering texts regarding socially engaged art. In this statement, Ala Plástica describes how they use direct interventions as their art-making method. Their long-term investment in space (specifically the Río de la Plata region in the AA Project) can be classified as “strategic manipulation”, achieved through the participation of Argentine locals. Additionally, Nato Thompson writes in his 2011 book “Living as Form” that the cultural and symbolic manipulation accompanying activism is similar to what can be seen in modern art. Taking in mind defined concepts allows Ala Plástica to adhere to the aesthetic responsibilities and principles of socially engaged art practices. Nicolas Bourriaud opened the discussion about relational aesthetics in 2002 referring to Situationist International as the pioneers of relational art in the 1960s by creating “constructed situations” or “simulated microtopias” that exhibit central themes of togetherness. This can be seen in Ala Plástica’s statement, as they refer to a “parallel universe”, which alludes to a symbolic “togetherness” in order to create a vision for the Argentinian community. The group is experimental, another characteristic of relational art, and their work is in perpetual flux. Their work acts to produce a catalyst of “organic objectivity shifts” with sustained interventions. How exactly this constitutes to aestheticism or how the symbolic potential of art is actually achieved through their work remains unclear with this statement alone, therefore I have diagrammed another statement of Ala Plástica’s concerning their artistic process:

“Utilizing dialogue and communication as a primary means, we have created unconventional artworks (…), and stimulated collective experiences to empower individuals to have a wider field of influence in their own political and biological environment.”

Ala Plástica website

With the aforementioned quote in particular, Ala Plástica zooms in on how they keep the symbolic potential of art (as per the last quote) and their intentions behind their artistic practice. I have dissected this quote in conjunction with their initial statement and established definitions of socially engaged art.

As Ala Plástica establishes dialogue and communication as inherent to the participation process of their projects, they give agency to their participants, ultimately embracing the idea of co-existence as a means to create. In pairing this with direct interventions and defined artistic concepts, they stimulate collective experience in a constructed/simulated situation, which, according to Thompson, is an act of strategic manipulation, and in my interpretation, is what Ala Plástica means by creating a “parallel universe”. Participatory art can — according to Claire Bishop in “Participation and Spectacle — Where are we now?” — communicate on two levels, namely to the participants and to the spectators. However, there must be a mediating third term that allows this very communication to take place — this we call the “spectacle” and define as the “permission of the experience to have a purchase on the public imaginary”. In this sense, we can see how Ala Plástica’s use of spectacle is grounded in the empowerment of their participants, which then clarifies what Ala Plástica views as the symbolic potential of art and how this is a component to their collaborative process.

THE AA PROJECT

The video above accompanied Ala Plastica’s installation in the exhibition GROUNDWORKS in 2005. It was not specifically made for the site-specific AA Project in the Río de la Plata region, but to showcase the project in an institutionalised gallery space as visual evidence of their work in Argentina.

Levels of social engagement

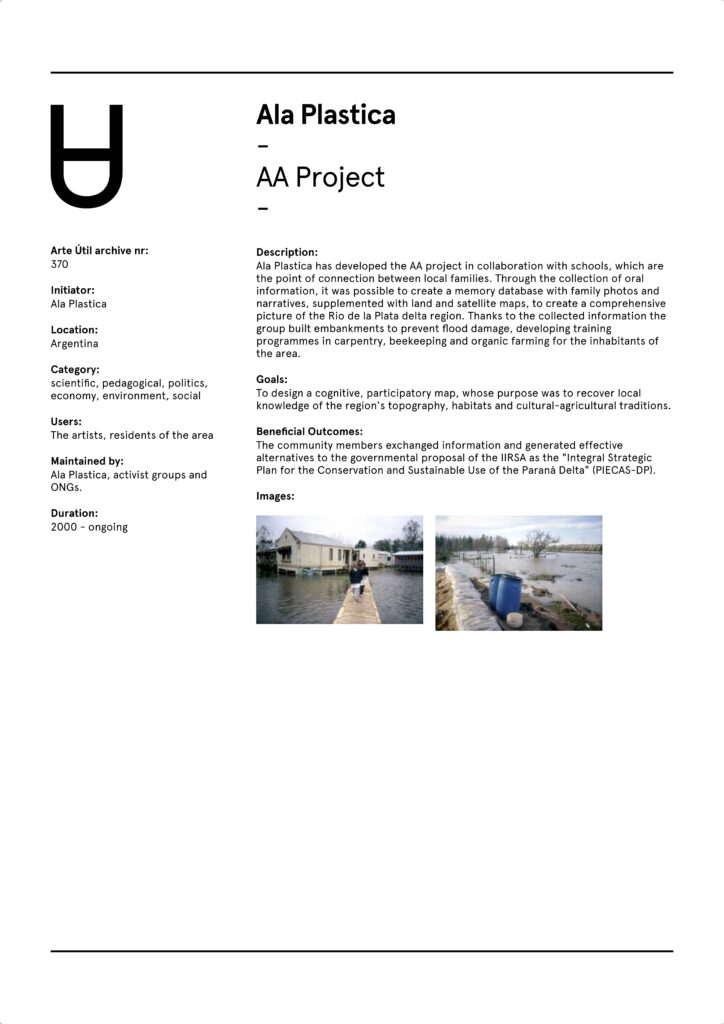

source: https://museumarteutil.net/projects/aa-project/

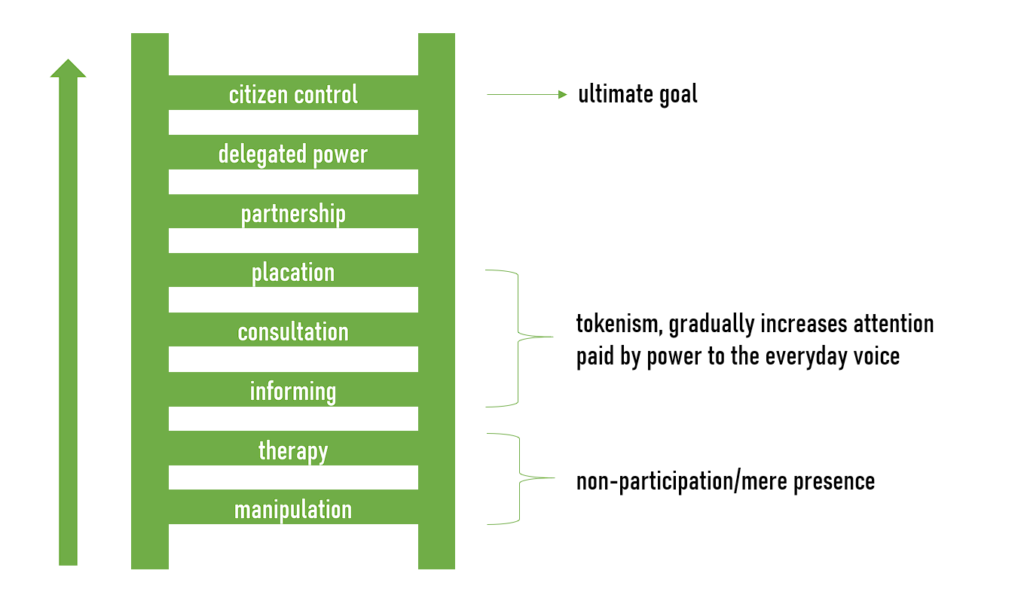

Above is an archived description of the AA Project by Arte Útil. Here, I investigate the levels of social engagement in the artwork in correlation with Bishop’s arguments on democratic socially engaged art and Latour’s own views on art in the Anthropocene. I want to make a suggestion apropos the archived description — that in support of Latour’s description of critical zones, the models of democracy in society are reflected in art. Bishop previously refuted the idea while looking at Christoph Schlingensief’s Please Love Austria (2000) and the Ladder of Participation, which is a suggested gauge for measuring the efficacy of collaborative artistic practice, wherein forms of citizen involvement and the degree of participation determine the overall value of a collaborative artwork. In Please Love Austria, for example, Bishop criticises this form of criteria by proving the work’s model of “undemocratic” behaviour of its participants corresponds to true democracy in Austria. She further notes it falls short of corresponding to artistic gestures, further stating that “models of democracy in art do not have an intrinsic relationship to models of democracy in society”. However, I noticed, that even though models of democracy in society and in art have their own complexities, it could be fallacious to completely alienate the two. As exhibited in the AA Project, both models of democracy are essential, and citizen control, as per the Ladder of Participation, is seen as the ultimate goal. For example, as written in the archive by Arte Útil, the beneficial outcomes include the generation of effective alternatives to the Argentinian government’s proposal of the The South American Regional Infrastructure Integration Project (IIRSA), giving power to the locals to reclaim control over their territory. Ultimately, Ala Plástica was able to incorporate models of democracy in society into the AA Project and make them parallel to — and not conflicting with — models of democracy in art.

With reference to previous positions on collaborative art provided the introduction, Kester reflects on levels of engagement while Juneja’s arguments have a direct correlation to Ala Plástica’s AA Project if we decide to apply her statements in that context. Recording “art history” in terms of “archive and vision” is somewhat analogous to the AA Project’s mapping procedure in the sense that data collection from locals was able to create a holistic visualisation of the Río de la Plata region, which can translate to Juneja’s arguments about how art history can also benefit from a more holistic (global) approach.

Collaborative art practice as a site for environmental activism

source: Arte Ùtil archives

” [The AA Project] mobilised new modes of collective action and creativity in order to challenge the political and economic interests behind large-scale development of the region.”

Grant H. Kester, The One and The Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art In A Global Context

Kester uses the AA Project in his 2011 book as a case study and writes about their project as an act of resistance against the Zarate-Brazo Largo rail complex, which was considered a threat to fishing and tourist economies, social services, and local employment. However, after researching more about the project itself, the AA Project is just one of many by Ala Plástica to counteract the proposed IIRSA, its roots tracing back to Spanish and Portuguese colonisation and the denomination of South American territories as a “global factory”. So, while in essence the AA Project had been established to specifically advocate against the rail complex, the entire body of work of Ala Plástica tackles the grander scheme of the IIRSA. Alejandro Meitin, one of the founders of Ala Plástica, wrote an essay for the Hemispheric Institute entitled “Urbanismo crítico, intervención bioregional y especies emergentes” that, according to the abstract,

“explores transdisciplinary strategies of critical urbanism that integrate artistic modes of thought and action to create contexts of resistance and transform reality.”

In the essay, Meitin explains their motives for their projects, writing that:

“In reality IIRSA is an accumulation and coordination of a great diversity of projects that already existed and now they are given a framework of regional vision that subordinates their social objectives to the logic of competitiveness. It is particularly surprising that most of the initiatives proposed by the new governments are the same, especially in Brazil and Argentina, as those that the neoliberal governments of the last decade of the 20th century attempted to implement and that their peoples in one way or another managed to stop or hinder through a broad debate generated and built from the communities and regions with strong activism from many civil society organizations in our regions.

translated from the original

According to Guy Debord (as mentioned by Bishop), a spectacle is “participation [rehumanising] a society rendered numb and fragmented by the repressive instrumentality of capitalist production.” We can relate Debord’s statement to the efforts of Ala Plástica by looking at the AA Project as symptomatic of a resistance against colonialist expansion and degradation of territory. However, is the acknowledgement of the project’s aesthetic value detrimental to its activist character? For that, we need to look at a few comparisons and the issue of institutionalisation of such artist/activist projects, which we will do so in the next chapters.

COMPARISONS

Levels of social engagement and activism can very well depend on local socio-political climates. For example, there is a disparity between regions in the Global South and the Global North, which results in differing methods of interventions and collaborative practices. This is one of the multiple reasons I hope to explore Ala Plástica’s use of collaborative practice as a potential model for other artist-environmentalist movements in the Global South, as established regimes and their relationship to such practices differ between the two hemispheres. Therefore, I would like to compare the execution of the AA Project to projects in the Global North and South, for which I have chosen to look at Park Fiction (Germany) and Moving Rainbow (China, Tibet) respectively.

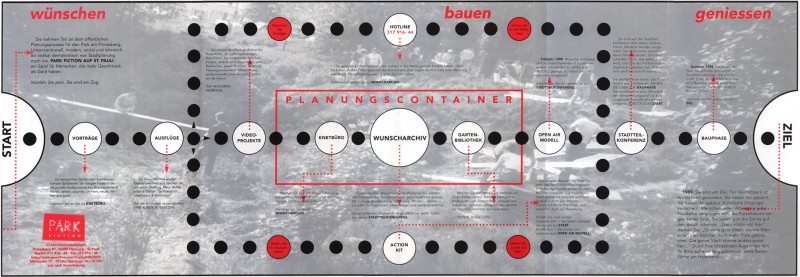

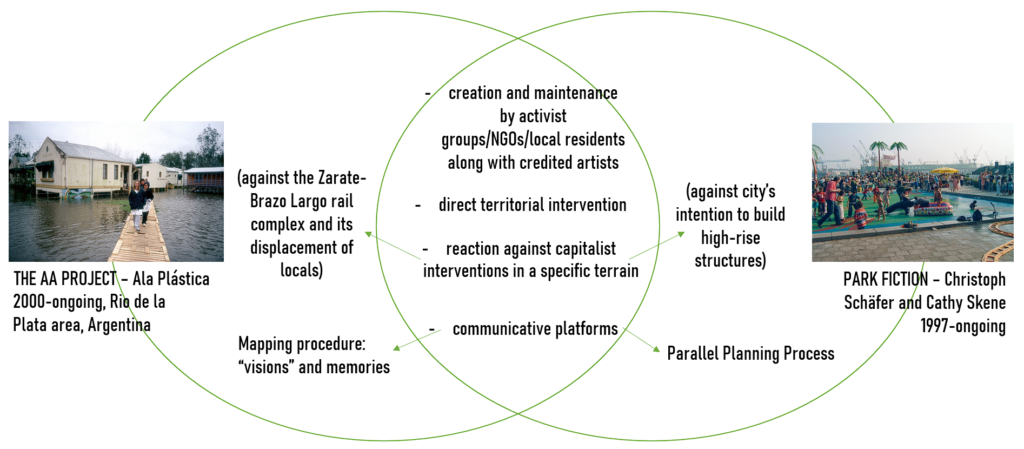

Park Fiction

At first glance, the AA Project (Global South) and Park Fiction (Global North) seem to have executed their respective projects in a similar fashion — the main difference lies in the importance of “terrain” in the AA Project and its role in local infrastructure. The methods of production, I could claim for example, are essentially identical, however the contexts in which these projects were conceived possess ever-so-slightly distinct concerns. Let me elaborate: both projects rely on the creation and maintenance by activist groups/NGOs/local residents along with credited artists, which is very self-explanatory for collaborative work. In both projects, there is direct territorial intervention as a reaction against capitalist/neo-liberal interventions in their respective localities. Ala Plástica affiliates their interventions with theories of territory and large-scale capitalist expansion (i.e. the Zarate-Brazo Largo rail complex and the IIRSA), while Park Fiction works against urban planning processes implemented locally (i.e. the city’s intention to build high-rise structures on the lot). Both projects use communicative platforms to achieve their artistic goals, and rely on participants to contribute to the infrastructural outcomes of their projects. Ala Plástica used mapping procedures to archive visions and memories of the locals as well as record traditions of cultural significance to incorporate into their programmes. Park Fiction had what they called a “Parallel Planning Process” in the form of a board game to attract residents of the area to engage in creating a blueprint for what is now known as the Gezi Park in Hamburg.

Moving Rainbow

In Fig. 14, for example, the contexts of AA Project and Moving Rainbow are seen as virtually the same. Both projects from the Global South emphasise human-nature relations and the importance of natural landscape, yet the execution of the following projects are different. An important aspect of both projects is the incorporation of local cultural tradition: AA Project and willow cultivation, Moving Rainbow and the colours of Tibet — this enhances the importance of participation and gives the locals a valuable role in contributing to the intervention. This approach is more personal compared to Park Fiction and embraces specific unifying aspects of their respective communities. Here, the participants directly affected in these critical zones engage in united labour as a reaction against “industrial colonisation”, and are provided opportunities for better livelihood conditions (i.e. better infrastructures in the Río de la Plata region, and more durable work equipment for truck drivers) as a result. Their forms of united labour, however, differ in terms of the timeframes of intervention. Xiong Wenyun’s intervention was temporary, and was only achieved while the trucks drove through mountainous highways, exhibiting, how Thompson calls it, a “tactical spectacle” that does not directly provoke the government. In other words, Xiong Wenyun might have found a loophole in releasing a statement against China’s trade dominance and environmental exploitation.

source: Three Shadows Photography Art Centre

INSTITUTIONALISATION

Groundworks

Fig. 17. Park Fiction at the Groundworks exhibition, 2005

Fig. 18. Ala Plástica at the Groundworks exhibition, 2005

source: Groundworks website gallery

I chose to explore the 2005 GROUNDWORKS exhibition organised by Grant H. Kester because I want to look at Ala Plástica’s scale of activism in artmaking by investigating its institutionalisation. As mentioned by Kester in the introduction to my essay, “art is trapped in the oscillation between challenging the institutional power and being institutionalised” while arguing the destabisilation of power as a paradigm shift in contemporary art. Both the AA Project and Park Fiction were featured in the GROUNDWORKS exhibition of 2005. To do that, they transformed their site-specific projects into installations. The works, as evidenced in the pictures above, had been curated to be situated next to each other in the exhibition, further hinting at their similarities. Interestingly, Bishop writes that “activist art sacrifices its aesthetic credibility on the ‘altar of social change’”. However, Jacques Rancière, as quoted by Bishop, states that shock and disruption are necessary prerequisites for authentic art, and that participation has potential for these types of conflict. Kester also writes that:

“(…) it is the procedure of distanciation and critique that constitutes the essential content of the contemporary aesthetic.”

Kester implies that contemporary art, in essence, has less to do with stylistics and more to do with identification and conflict of power. Before being placed in a gallery, the AA Project and Park Fiction were projects directly involved with social change, as well as having aesthetic credibility (we can argue this through the ideas of Rancière and Kester). Once something like the AA Project or Park Fiction or Moving Rainbow (for context: it became a series of photographs exhibited numerous times) becomes intsitutionalised and placed in a gallery/exhibition, does that eliminate its activist character?

One last comparison: Equation of State

Equation of State by Martha Atienza is an example of a circumstance where institutionalisation is not a risk, but inherent to collaborative art practice. Like Ala Plástica, Martha Atienza of the Philippines filmed and turned her collaborative practice into an installation she presented for the 2019 exhibition Equation of State in Silverlens Galleries, Makati, Philippines. While her work serves as a reaction to the removal of Bantayan Island’s Wilderness status (on top of its struggle over land-use and ownership), Atienza does not create a direct response nor enact direct social change. The intention of the work, like Rancière puts it, is to shock and disrupt. She additionally placed a robotic mangrove installation (as seen in the video above) to call out the mismanagement (by the government) of the mangrove forests that protect Bantayan Island and its residents from natural disasters. The collaboration is not meant to sustain its participants but to relocate and relay regional struggle to the centralised government municipality of Metro Manila. She stages the intervention in the confined white walls of a gallery space in an attempt to protect her work, but also to indirectly challenge environmental politics. Her work interestingly adheres to Bourriaud’s concept of “togetherness” by working with residents of Bantayan, chews it, swallows it, and regurgitates it as an outcry to the Philippine government’s handling of environmental issues, adhering to Bishop’s counter-concept of “antagonism”. The main difference between the “institutionalisation” of the AA Project and of Equation of State, is that on the one hand, the AA Project is set up in GROUNDWORKS as a three-dimensional progress report and aims to explain and present their motivations, methodology/process, and results. Equation of State, on the other hand, is both a report of the happenings in Bantayan Island, and a request for the viewer “to question environmental management and the almost invisible hand of legislation that governs territorial land and waters.” (Jake Atienza, Equation of State catalogue) The AA Project is thus a showcase of democracy, while Equation of State is a call to it.

CONCLUSION

Can collaborative art groups like Ala Plástica serve as a model for other artist-environmentalist movements in the Global South?

To answer the question I had posed in my introduction, I would like to reflect on Juneja’s past arguments for using a transcultural perspective, specifically the following:

- There is an urgency for art that can function as a domain of symbolic actin, as an area of political and creative practices, of affirmative, performative citizenship rather than simply a reactive aesthetic

- [Transculturation] seeks to avoid an overemphasis on polarities and oppositional structures by paying greater attention to multiple relationalities that unfold beyond the coloniser-colonised divide,

- HOWEVER: There must be an examination of the specific dynamics between distance and proximity; to then unravel specific issues and conditions of the particular locality, where modernist ideas became a productive site of confrontation and negotiation

In summary, Juneja writes:

“A transcultural perspective therefore means that we study a combination of comparison and entanglement. It also means negotiating scales beyond the local and the global to navigate multiple scales, indeed to grapple with scale from the perspective of actors for whom it becomes a mode of self-positioning.”

This provides reason to determine that whether collaborative groups like Ala Plástica can serve as a model for other artist-environmentalist movements in the Global South may still be heavily debated.

Issues to consider

As we have noticed in our comparisons, there is a difference in treatment of socially engaged (environmental) art discussions in the Global South (for example vs. the Global North), regarding the following issues:

- Colonial continuities within questions of environment, territory, and the Anthropocene

- Political limitations; potential effects of the local socio-political climate and its acceptance of public (artistic) confrontation; non-governmental provocation vs. governmental provocation

- Antagonism and aesthetic autonomy: is the attempt to separate aesthetics a privileged domain of critique?

With these issues in mind, we can conclude that the answer requires a multi-faceted and interdisciplinary approach. The importance of looking at this with respect to the Global North-South divide lies not only within their differing treatments of climate activism to address colonial continuities, but also within the use of environmentalist action as reparation in the Global North (cf. Sharma) versus restoration and reclamation in the Global South. What seems prevalent in the Global South, for example, is the provision of infrastructure and/or help to the participants. The main difference between participatory works in the Global South and the Global North is the creation of opportunities for their participants with long-term benefits, as well as incorporating elements of culture and tradition. In the Global South, the idea is not to transform but to improve, and Ala Plástica does so and claims to do so in an experimental manner. Nonetheless, their methods might not be as accessible to other groups. In China and the Philippines for example, interventionist methods, whether artistic or not, can be sensitive to the political climate. The current situation in the Philippines for example (to place this argument in a more relevant scope), suggests that interventionist artistic practice can be punishable by law (cf. 2020 Anti-Terror Law). This would, of course, highlight the “activist” nature for certain viewers and spectators, however, issues of reception can, as Bishop argues, threaten its aesthetic credibility. Again the “model” issue is brought to the fore, as in some areas Ala Plástica would be difficult to emulate. This is where the “institutionalisation” of environmentalist actions can act as a protector of concepts where a long-term investment in space is unattainable.

It is thus my belief, that the characteristics of a true ideal collaborative artistic and environmentalist practice in the Global South would incorporate Ala Plástica’s regenerative procedures and respect for local tradition to create better livelihoods for their participants, but also Xiong Wenyun’s and Martha Atienza’s tributary approach to artistic institutions as a means of emphasising the aesthetic value of their interventions and thus use a gallery’s walls as “protection” from authoritarian vindication.

However, as Jason Miller argues in his article “Activism vs Antagonism: Socially engaged art from Bourriaud to Bishop and beyond”:

“(…) aesthetic antagonism is the problematic assumption that conscience-raising has not only inherent ethical value, but also an ethical priority that shields the artist from any other form of ethical critique.”

When considering Miller’s arguments about aesthetic antagonism, it is incredibly important to note that the institutionalisation of interventionist work must not and should not excuse any artist or artist group from violating ethical values and principles. Artistic provocation, will, and always will, have its moral influences on its spectators. In whatever way the artist chooses to use the privileges of institutionalisation to “protect” their work will remain their decision and become, all the same, subject to scrutiny.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ala Plástica. ‘Ala Plástica’, 2016. alaplastica.wixsite.com/alaplastica/about.

- Atienza, Jake. Martha Atienza: Equation of State. Makati City: Silverlens, 2020.

- Bourriaud, Nicolas. 2002. “Introduction.” In Relational Aesthetic, 11-24. Dijon-Quetigny: Les Presses du Réel: 2002.

- Bishop, Claire. 2004. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October 110: 51-79.

- ———. 2012. “Participation and Spectacle: Where are we now.” In Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011, edited by Nato Thomson, 34-45. New York: The MIT Press.

- Coleman, Vera. ‘Emergent Rhizomes: Posthumanist Environmental Ethics in the Participatory Art of Ala Plástica’. Confluencia 31, no. 2 (Spring 2016): 85–98.

- Future Learn. ‘Case Study: Moving Rainbow’. Online Course, n.d. futurelearn.com/courses/socially-engaged-art/0/steps/23853.

- Gezi Park Fiction St. Pauli. ‘Park Fiction – Introduction in English’, 10 December 2012. park-fiction.net/park-fiction-introduction-in-english/.

- Goodman, Jonathan. ‘Xiong Wenyu: Ten Years of Moving Rainbow’, 31 July 2008. artcitical.com/2008/07/31/xion-wenyu-ten-years-of-moving-rainbow/.

- Juneja, Monica. 2018. “‘A very civil idea…’: Art History, Transculturation, and World Making – With and beyond the Nation.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 81: 461–85.

- ———. 2020. “Mikrogeschichten: Die Routen des Transkulturellen Modernismus – Microhistories: The Routes of Transcultural Modernism.” In Museum Global: Mikrogeschichten einer ex-zentrischen Moderne – Mircohistories of an Ex-centric Modernism, ed. by Susanne Gaensheimer et al., 37–46.

- Kester, Grant H. ‘Collaboration, Art, and Subcultures’. Caderno SESC_Videobrasil 2 (2006): 10–34.

- ———. The One and The Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art In A Global Context. Duke University Press, 2011.

- Latour, Bruno. ‘Anthropocene Lecture: Bruno Latour’. Lecture presented at the Anthropocene Lectures, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 4 May 2018. https://www.hkw.de/en/app/mediathek/video/63344.

- Meitin, Alejandro. ‘Urbanismo Crítico, Intervención Bioregional y Especies Emergentes’. Emisférica 6, no. 2 (n.d.). https://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-62/6-2-essays/urbanismo-critico-intervencion-bioregional-y-especies-emergentes.html.

- Miller, Jason. 2016. “Activism vs. Antagonism: Socially Engaged Art from Bourriaud to Bishop and Beyond.” FIELD: A Journal of Socially Engaged Art Criticism 3 (Winter): 165-183.

- Sharma, Mihir. ‘An Open Letter on the Unthought Contradictions of Doing Climate Activism’. Stillpoint Magazine, 22 May 2020.

- ———. ‘Decolonizing Climate Activism in the Global North: Whose Crisis?’ Zoom Lecture presented during the lecture series Colonial Continuities: Spotlight On…, 28 April 2020.

- Thompson, Nato. 2012. “Living as Form.” In Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011, edited by Nato Thompson, 16-33. New York: The MIT Press.